Plastics

14 minute read

Our relationship with plastics will change – first gradually, then suddenly

From lead to mercury, humankind has adjusted to life without materials we once considered essential. What can these stories tell us, as we’re finding a way out of our current entanglement with plastic – and establishing a new, circular relationship with it?

Expect to learn:

How companies are working to make plastic more sustainable.

What are some of the hidden psychologies that block change.

How radioactive isotopes were once welcome in our wardrobes.

In Ernest Hemingway’s 1926 novel, The Sun Also Rises, one of the characters is asked how he went bankrupt. “Two ways,” he replies. “Gradually and then suddenly.” It’s a line often quoted by analysts of business and politics to explain the way in which change, when it happens, can feel sudden – but has, in reality, been building for some time, had we only recognised the signs. It’s a dynamic that fascinates forecasters and historians, economists and scientists. But it can also be instructive in conversations around our current world; helping us to think beyond our own assumptions. Change happens. First gradually, then suddenly.

The age we live in can be defined by many things: the internet, antibiotics, and space exploration, to name a few. But in terms of the mark we leave behind, perhaps the biggest claim to future historians will be laid by our reliance on plastic.

Change happens. First gradually, then suddenly.

This reliance, on its current terms, is partly unsustainable. So can studying the ways in which we fundamentally rethought our relationships with similarly indispensable materials in the past shed any light on where we are in 2020?

Mementoes of change

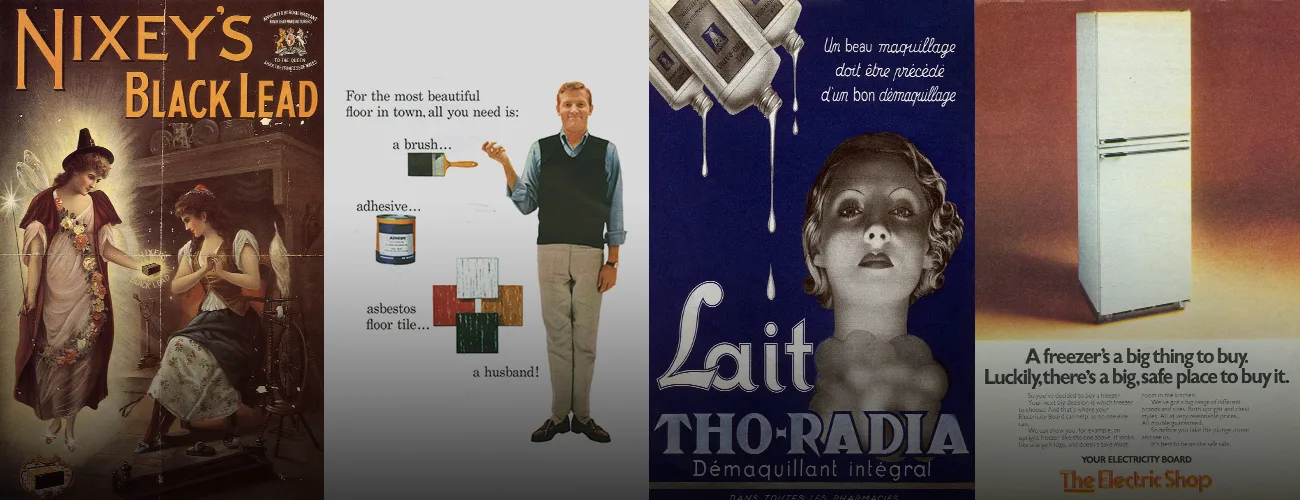

Old advertisements for consumer products give a surreal glimpse at a world where dangers were the standard of modern living: asbestos in clothes irons, radioactive watch dials, baby thermometers with mercury. How did we go from celebrating these materials to having a very different relationship with them? And could plastics – not a toxic material like asbestos or mercury, but one that currently causes serious global problems in the form of plastic waste ending up where it shouldn’t and severely harming our environment – ever follow a similar path?

“A thoroughly reliable and practical luminous watch”, proclaims a 1918 advertisement for watches. With dials that lit up in the dark, these watches were promoted as a feature for military use and sold as fashion accessories. The glow-in-the-dark watch was the smartphone of its day: useful and practical; a bit of a novelty, and most certainly a status symbol. There was a catch. The luminous effect on the watches was achieved by applying paint containing radium and zinc sulfide to the hands and dials. Energy released from the radioactive radium Ra-226 isotope produced a phosphorescent glow; but that same radioactivity also caused radiation poisoning among the workers who painted the dials. In the United States, some of these “Radium Girls” sued their employers for exposing them to unsafe working conditions. It took several court cases and deaths for labor conditions to change, and eventually the production of radioactive clock faces ceased entirely. Now, different, safer solutions like phosphorescent paints or digital displays make modern timepieces equally visible in the dark. This was not the only time that awareness of the risks of a material in daily use was changed by health considerations; or that these changed our attitudes to what initially seemed like a catch-free convenience.

These materials made our lives easier and convenient and changed our standards of living

Today, the word asbestos probably reminds you of old building materials that pose a health risk if they’re damaged during renovations. But in the mid-19th century, well before those risks were known, asbestos was included in absolutely anything that could possibly benefit from its insulating properties: bricks, textiles, furniture, fire blankets, clothes irons, brake pads, fire fighters’ outfits. If it could get hot, add some asbestos for safety. But the immediacy of the safety it offered balanced by a longer-term drawback. Inhaling asbestos fibers can cause lung damage, cancer or mesothelioma. Indeed, people have been aware of these health risks since the early 20th century, when asbestos miners and textile workers started to fall ill. In response to medical evidence proving the link between asbestos and disease, regulations for asbestos use were gradually put in place, as industries started to shift to other types of insulation materials.

Over the course of the last half of the 20th century, many countries have passed legislation to limit the use of asbestos or phase it out completely. Knowledge of the material’s toxicity is widespread today and exposure to it is minimized. We may wonder what we were thinking in the beginning? The fact is, however, that materials like asbestos and radium seemed like a good idea at first. Like lead – so fundamental and useful to Western society for so long that its Latin name plumbum gives us the very word ‘plumbing’ – they made our lives more convenient, changed our standards of living and contributed to economic progress.

And then, seemingly suddenly, the drawbacks seemed overwhelming.

These are all materials whose benefits were balanced by drawbacks. And they all followed the same pattern. First, the drawbacks were not known. Then they were not widely discussed. Then, they were not considered sufficiently important to alter our consumption. Then, seemingly suddenly, the drawbacks seemed overwhelming. At that point, we made large-scale changes and looked for more sustainable solutions. And the fascinating part is, that the story unfolds in ways that are different on the surface, but ultimately, similar every time.

Studying the patterns of change

These weren’t always fast or easy changes. Because far from just deciding to use one material instead of another, we had to completely rethink what we considered ‘normal’ and to redefine the idea of ‘useful’. In that process, there was often a period where most people carried on with the status quo, while a small group of people rang the alarm. Not too long ago, the phasing out of chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) followed a similar trajectory. One of the major environmental concerns in the 1990s was the hole in the ozone layer. In 1974, chemists revealed that the CFCs commonly used in consumer products such as hair sprays and refrigerators were drifting up into the stratosphere and gradually removing ozone from the ozone layer. The ozone layer absorbs UV radiation from the sun. Without it, life on Earth would not be possible, so keeping it intact was a matter of great concern.'

The success of the CFC ban is a great example of what can be achieved when habits and production methods change

Consumers became concerned about the high amounts of CFCs used in certain products, and demanded change. Companies started producing CFC-free sprays in response to consumer demands. But when a research expedition found a significant hole in the ozone layer above Antarctica in 1985, the urgency became even more apparent. In 1987, countries around the world collectively signed the Montreal Protocol, agreeing to phase out CFCs. Since then, many countries have banned CFCs entirely. New fridges use a different type of coolant, and hairsprays no longer include CFCs. What’s more, the ban worked. In late 2019 NASA reported that the hole in the ozone layer was the smallest it had ever been since its first discovery. The success of the CFC ban is a great example of what can be achieved when habits and production methods change. But it’s also a good reminder of how we went from being completely dependent on CFCs (even if just for your fridge at home) to being not just able to cope, but perfectly fine without them. In all the examples above, the story is the same, at least in its early stages. We found a convenient use for a material. We started using it in consumer products. We got used to having these items and started using them excessively. We then learned about the long-term risks. But what’s really interesting is what happened after that. Once we knew the risks of radium or asbestos or CFCs, there were initial waves of protests and consumer-led action groups. These protests led to pressure on brands and manufacturers.

That stage was followed by policy changes. Then came new manufacturing processes. And eventually, a new normal. In that ‘new normal’ we simply can’t imagine that we once enthusiastically over-consumed these products for our everyday purposes.

We still use, and need, lead and radium for very specific things, but they are not our first resorts

We still use, and need, lead and radium for very specific things; we just don’t slather them all over our homes, or use them so liberally anymore. They are not universal first resorts, and when they are used, strict safety standards are followed. Instead, we use them with clarity and thought, around their specific drawback. And in the meantime, we have developed alternative products. Watches light up in the dark using electricity, not radium; insulating materials aren’t made of asbestos; fridges and hairspray work without CFCs.

We did not have to give up our conveniences. It just took time for our thought patterns to adapt.

But we also have a new mindset. Finding different ways to manage our usage of these materials didn’t mean we had to give up our conveniences. It just took time for our thought patterns to adapt. And that is where there is often most initial tension. Many of these changes, away from certain ubiquitous materials, involve a phase in which the drawbacks are known, yet refusing, regulating or reducing use of the materials is considered radical. Take chlorofluorocarbons as a fairly recent case. By the 1980s, people knew about the risks of CFCs. And logically, it should have been an easy consumer choice to refuse products in aerosol cans. At least with the benefit of hindsight, it sounds easy now. But back then it meant not conforming to the mainstream consensus. (In a strange twist of fate, the inventor who pioneered the use of CFCs was American scientist Thomas Midgley; the same man who in 1924 had introduced tetraethyl lead into petrol, and campaigned on the basis that it too was “perfectly safe” and free of downsides.)

We completely changed our mindset. Consensuses change. Gradually, then suddenly

In the 1980s and 1990s, protests against CFCs, like the warnings about the hole in the ozone layer, initially came mainly from activist groups. And aligning with them was initially a hard step for people to make in their minds. But the message gradually got through. Today, we can’t even imagine how we used CFCs so liberally and in complete disregard of the ozone layer. We completely changed our mindset. Consensuses change. Gradually, then suddenly.

The Age of Plastic… and how it is changing

So what are our current age’s conveniences – the seemingly immovable pillars on which our own lives are built? Materials which we feel we cannot live without, just as life without lead was unthinkable – and yet our reliance on them may seem equally strange to those who come after us? Many would say that our plastics consumption today could be a likely contender. Not because plastics are toxic or harmful to health similarly to asbestos or lead, but because their excessive use and careless treatment at the end of their life cycle nevertheless carry environmental and possibly also health risks. Plastics are everywhere in our homes, from our food packaging to our household products, and in our cities and surroundings, in cars, buildings and even in our shoes and clothing. Plastics are manufactured globally with a speed that is expected to grow significantly. Yet we already know that despite providing significant benefits in certain applications, their excessive and careless use in others is leading to trouble. The fact is, however, that we’re already in a transition period at the moment, when it comes to plastics. We’re already seeing changes in consumer habits – such as recycling household plastics or refusing plastic bags at stores, if they are even offered. Meanwhile companies are exploring ways to switch to more sustainable plastic materials, produced with renewable or recycled raw materials, and searching for ways to recycle the plastic we no longer use to cut down on the negative impact of plastics entering the environment.

What can our previous experiences teach us about the shape of demand going forward?

Companies such as Neste are developing solutions for making our plastic use more sustainable. Together with its partners, Neste is developing chemical recycling to enable recycling of those plastics that currently cannot be recycled with conventional mechanical recycling. This helps create value for plastic waste and ensure that more plastic is reused and recycled and less discarded carelessly.

Furthermore, chemically recycled plastic waste can be combined with renewable plastic feedstocks to produce new plastic while cutting the industry’s reliance on virgin fossil oil. As plastics are a supreme material in many of their applications, a world without plastics may not be what we need to aim for. During Covid-19 pandemic, for example, hygienic plastics in medical and healthcare applications and packaging are simply saving our life. But otherwise, measures such as Neste’s, alongside global efforts to limit the use of non-essential and single-use plastics, are needed to limit their short- and long-term environmental impact.

But what of the arc of consumer and business attitudes? What can our previous experiences – with lead and the rest – teach us about the shape of demand going forward? Going without plastic entirely is somewhat of a fringe movement at the moment, similar to refusing to use hairspray in the 1980s. But the changes in legislation are already taking place: many single-use plastic products, such as plastic straws, plates and cutlery will be banned in the EU by 2021.

Additionally, forerunner companies are already adopting new, more sustainable plastics manufacturing methods. So we’re already seeing some changes. But it is not just about plastics production that is changing. Ultimately, we’re becoming aware that our current use of plastics is unsustainable. Just like we now can’t imagine ever having needed or wanted a radium watch or a can of hairspray with CFCs, we might one day bemusedly look back on how many new plastic bags we used carry home from our trip to a supermarket or how we used to toss all our plastic waste into our mixed waste bin.

Although such change of attitude and behavior seems to have come rather suddenly, it is still an ongoing process. What is important is that it has started, and consumers, governments and the industry are all looking for solutions – ways to produce plastic from renewable raw materials and existing plastic waste instead of crude oil, and regulations that would insure that we would not use plastics to make ‘just about anything’, but instead choose to use plastic when it is the supreme and most sustainable choice. To see the process in action, just look back at how strange and wrong advertisements for disposable products seem today. From the 1950s to the 1990s, the throwaway nature of certain products was often their selling point. You don’t have to carry your lunch box or cup around; just throw them away! From disposable rain ponchos to cameras – cheap and temporary has often been a selling point.

Like said, mentalities are shifting. And for many, they have already shifted decisively. Businesses and, perhaps more importantly investors, are starting to realize that change is happening and one needs to work with it – or even accelerate it. An internationally broadcast award-winning IKEA ad from 2002 featured a lamp that was thrown out with the garbage, and the Swedish commentator declaring that “Many of you feel bad for this lamp. That is because you are crazy!”

In 2018, IKEA released a sequel that nicely reflects our changing attitudes. In the new ad, the original lamp was picked up from the street and found a loving new owner. If the contrast is stark in retrospect, perhaps it is no more so than a lot of the other changes in attitudes, cultural and otherwise, that have happened over the past two decades. It is the nature of change that it is hard to notice it as it happens. Just as it was with leaded petrol, CFCs and others, so it is with wider issues, such as climate change. Instead of giving up plastics entirely, we must continue to change the way in which we think, use, and make plastics. From change being unthinkable, to being inevitable. The mindsets shift. First gradually, and then suddenly.

Credits:

Dr. Eva Amsen, a science writer and communicator whose work has appeared on Forbes, Nautilus and The Scientist. Twitter