Innovation

17 minute read

A leap into the unknown: how ‘design fiction’ is shaping our future

As the prizes for innovative and sustainable businesses grow, more companies are using science fiction and creative thinking as an extension of their Research and Development teams.

Expect to learn:

What design fiction is and how it works.

How design fiction is powering the research and development of the world’s most forward-thinking companies.

The possibilities and upsides of utilizing futurologists and science fiction writers within big businesses.

The most interesting examples of how science fiction created decades ago is shaping our current reality.

The funny thing about innovation is that nobody ever sees it coming. But then as soon as it’s arrived, it seems obvious.

An 1884 article in The Times reported that every street in London would eventually be buried under a layer of ”nine feet of horse manure”. The conclusion, based on available projections, was sound. London was growing rapidly, and horse-drawn transport was multiplying. And the mathematics came to nine feet.

But there were wider changes that this prediction failed to take into account. This rapid urbanization, and the demand for more transport from more people and goods, in a form that was easier to build, use and store, would spur an innovation that would render those projections utterly meaningless. That innovation was the motor car. The days of manure – and horses themselves – on London’s streets were numbered.

It’s easy to smile. But the very innovator whose futuristic machine would spawn this disruption, the German inventor and automobile pioneer Karl Benz, was about to fall into the exact same trap. In 1898, he predicted that the world would never have more than one million cars in it. The reason he gave was that the supply of chauffeurs was finite. Benz could invent the automobile. But like all of us – innovators or not – he was incapable of imagining the vast social, economic and political changes that would render the chauffeur irrelevant in the coming 20th century.

Disrupt or be disrupted

But hindsight is always 20/20. And life, as philosopher Søren Kierkegaard said, can only be understood backwards; but it must be lived forwards.

But for business leaders intent on innovating and avoiding potential disruption, ever accelerating innovation cycles mean letting go of some of the comfortable certainties of projections from existing norms. In the adage attributed to Benz’s contemporary, industrialist and business-process innovator Henry Ford: ”If I had asked people what they wanted, they would have said faster horses.”

"Life can only be understood backwards, but it must be lived forwards."

Ford was able to think beyond the moment – not to be bound by what had gone before. This is an ability that Toby Heaps of sustainability monitoring organisation Corporate Knights identifies among the leaders of today’s most sustainable businesses.

”There are leaders at the top of [the world’s most sustainable] organisations who are taking a stand on what the future looks like,” he told us on the phone from the Corporate Knights office in Toronto while preparing the Global 100 sustainability Index report for 2020. ”They do not just go with the flow. They are what I would term future makers, not future takers.”

It turns out that forwards – outside of their industries and into the kinds of hypothetical future scenarios more familiar to science fiction – is where some of the world’s most innovative companies are now directing their research. They do this, not by projecting current trends, but by envisioning hypothetical future consumerscapes, products, challenges, rivals, and opportunities, and playing them out imaginatively, before any operational work begins. This is sometimes called Scenario Planning.

"The world’s most innovative companies are now directing their thinking into the far future."

This need for all businesses to ‘scenario plan’ is the basis of the work done by Oliver Freeman of the University of Technology Sydney’s Business School, and Richard Watson of London Business School. Their classic 2012 book Futurevision: Scenarios For The World In 2040 attempts to take business leaders out of the incremental march forward, and get them thinking about the far future.

The book is full of thought experiments. Consider this one from the point of view of an innovation team in 2020. ”How, for example, might an oil price of $200 per barrel change the world? Perhaps people and products would move around less frequently, or the high price of food would lead to an unexpected decrease in obesity. What if we invented a new technology based upon photosynthesis that made energy almost free?”

Perttu Koskinen leads up Neste’s Innovation, Discovery and External Collaboration unit. He sees the value in stepping away from the here-and-now, describing heading the department as ”taking a great leap into the unknown.” Neste is in the business of combating climate change, one of the world's greatest challenges. And that means embracing this leap.

"Hypothetical scenarios are only ever as rich as the people imagining them."

One can see Koskinen’s point. Had you told anyone just a few years ago that in 2020 commercial airliners and diesel vehicles would routinely be running on fuel that was made from waste fats, they would likely have called it fantasy, or science fiction.

Ironically, fantasy is precisely what companies worldwide are turning to for the next wave of innovation. Because hypothetical scenarios are only ever as rich as the people imagining them. And this is where Design Fiction comes in.

Reading the future

The next time you hold an iPad, consider this: such a tablet features in Stanley Kubrick’s science-fiction masterpiece 2001: A Space Odyssey, a 1968 film that also foresaw Skype, credit cards and space tourism.

The developers of new technologies taking inspiration from science fiction – or, to use its more academic term, speculative fiction – is nothing new.

"The path from science fiction fantasy to real-world is more well-travelled than most people realise."

Speculative literature is full of theoretical innovations and imagined technologies that later solidify into reality. Isaac Asimov, Arthur C. Clarke, Philip K. Dick, and William Gibson – the man who coined ‘cyberspace’ and ‘hackers’ – became globally famous for predicting the future with the technologies they envisaged. Or perhaps more accurately, for spinning into existence a huge number of possible future technologies, ideas and ways of living on our planet, which entered culture and inspired businesses to make real-world technological investment.

In speculative movies and in novels, great thinkers with vast imaginations have come up with countless ‘What if?’ scenarios, unburdened by the practicalities of making them work. But this unburdening is also about slipping free of the shackles of assumption worn by people too close to the project, the industry, the time and the place.

"Writers of science fiction are now employed by the likes of Tesla, Google, Disney, Microsoft and Apple."

Robotics are everywhere in industry, but the word was the invention of Czech playwright and novelist Karel Čapek, whose hit 1921 play Rossum’s Universal Robots imagined humanoid servant machines, and named them with the Czech word robota, meaning drudgery or menial work.

And it’s not an exception. The path from science fiction fantasy to real-world tech is more well-travelled than most people realise. The Taser stun gun, devised in 1970 by former NASA engineer Jack Cover, was directly inspired by Cover’s favourite childhood novel. The novel by one Edward L. Stratemeyer, Tom Swift And His Electric Rifle, was one of a boys’ adventure series, written in 1911. How closely did the book’s futuristic zap-gun inform the modern-day invention? The very name TASER is a simple acronym of Thomas A Swift’s Electric Rifle.

As the Harvard Business Review said of Kodak: ”Where they failed was in realizing that online photo sharing was the new business, not just a way to expand the printing business.” Kodak had acquired an online photo sharing platform, Ofoto, as far back as 2001. But in that pre-Myspace (2003) and pre-Facebook (2004) world, the photo developing giant could not conceive that sharing images online would be anything more than a way to get photographs sent for print. The ”Kodak Moment” – once the company’s slogan for precious memories captured on camera – is now a phrase for any corporate giant that fails to see the future coming and pays the price.

With the rewards so rich, and the perils of disruption so great, it is no surprise that companies hire these imaginative minds to create theoretical simulations of their business’s future.

Writers of pure science fiction – in its corporate-funded guise as design fiction – are now employed by the likes of Tesla, Google, Disney, Microsoft and Apple. Their value is in generating these visions of the future themselves; getting there before reality does, in the form of disruption or competition. The company gets to keep the intellectual property rights for the scenario into the bargain.

Enter a new term for the harnessing of the imagination to stimulate innovation: ‘design fiction’. And it’s currently powering research and development in some of the most innovative companies on Earth.

Using science fiction as an R&D aid

Design fiction takes an object, or idea, and examines its potential, its pitfalls, and its possible applications and future development, by creating a full narrative world around it.

As in science fiction, the imagined future object, and the world around, should feel authentic. They should have their own principles and systems and be governed by firm rules. The phrase ‘design fiction’ was first used by Hugo award winning author Bruce Sterling in his 2005 book Shaping Things. ”Design fiction is the deliberate use of diegetic prototypes to suspend disbelief about change”, says Sterling. ”It means you’re thinking very seriously about potential objects and services and trying to get people to concentrate on those rather than entire worlds or political trends or geopolitical strategies.”

"That would be cool if it existed."

Asked to give an example, Sterling opts for the tablet in 2001: A Space Odyssey. ”The guy’s holding what’s clearly an iPad,” he says. “It just really looks like one, right? This actually showed up in the lawsuits between Samsung and Apple. That’s kind of a successful design fiction in the sense that it’s a diegetic prototype. You see an iPad in this movie and your response is not just, ‘Oh, what’s that?’ but ‘That would be cool if it existed.'"

In practice, that means companies interested in exploring new ideas; running through any unforeseen consequences of their plans, or pre-empting any Black Swan events, are hiring futurologists and science fiction writers to help them envision and simulate hypothetical futures more authentically.

Some choose to release their design fiction on a controlled basis, for the same reason that aircraft and car makers show concept models: not to sell it here and now, but as test balloons for potential future directions – preparing consumers and innovators alike for concepts that will one day become actuality. Microsoft has long placed prototypes of its future technologies in Hollywood movies, so that the public will better accept them when they, or something like them, finally arrive to market.

But this corporate-sponsored design fiction serves far deeper purposes. One of the most common is to explore how these products exist within the world around them, and the potential ethical implications.

"Microsoft has long placed prototypes of its future technologies in Hollywood movies."

In his 2009 essay Design Fiction: A Short Essay On Design, Science, Fact and Fiction, technologist, business consultant and Internet of Things pioneer Julian Bleecker writes, ”We can put the designed thing in a story and move it to the background as if it were mundane and quite ordinary — because it is, or would be. The attention is on the people and their dramatic tension, as it should be.” The Internet of Things itself is currently the subject of much design fiction, as companies wrestle with the implications, not just of technology, but of data laws and societal attitudes on their visions for the networked home.

Indeed, a large part of the job of science-fiction writers is to explore the pros and cons of technologies, ideas, ways of doing things – and how they contribute to our future, and that of our planet. Bleeker writes of ”creative provocations, raising questions, innovations, and exploration.”

”With the development of new biotech and genetic engineering, you see authors like Margaret Atwood writing about dystopian worlds centred on those technologies,” says Massachusetts Institute of Technology researcher Sophia Brueckner, who in 2013 teamed with fellow instructor Dan Novy to offer a course entitled Science Fiction to Science Fabrication at the MIT Media Lab in Massachusetts. ”Authors have explored these exact topics in incredible depth for decades, and I feel reading their writing can be just as important as reading research papers.

”Brueckner and Novy’s students are tasked with creating functional prototypes inspired by books, films and videogames. The class is also encouraged to engage in discussions on the ethical implications.

”Science fiction is incredibly relevant to the work going on at MIT,” Brueckner told The Atlantic. ”The Lab is made up of many different research areas like Biomechatronics, Tangible Media, or Fluid Interfaces, for example. Each of these groups has a corresponding subgenre of science-fiction, often one whose authors have explored related topics for decades. These authors do more than merely prophesy modern technologies – they also consider the consequences of their fictional inventions in great detail.

"Science fiction writers explore the pros and cons of technologies and ideas – and how they contribute to our future, and that of our planet."

Futurologists in the boardroom

A giant leap for corporate culture, perhaps; but from there, it was only a small step to companies inhousing these minds.

Production company DreamWorks is one of those to employ teams of MIT-style cross-discipline futurologists to generate design fiction in support of its business as well as individual creative projects. One of the most famous of these – not to mention star-studded – was hired for Steven Spielberg’s Minority Report (2002).

This science-fiction neo-noir, based on Philip K. Dick’s 1956 short story The Minority Report, is set in 2054. For this project, intent on portraying an authentic-feeling future and trialling window screens and issues around intrusive data shadows and AI, Spielberg invited 15 experts, including author Douglas Coupland, architect Peter Calthorpe, computer scientist Neil Gershenfeld, biomedical researcher Shaun Jones, computer scientist Jaron Lanier, and former MIT architecture dean William J. Mitchell, to a hotel in Santa Monica for a three-day ”think tank”. This think tank was tasked not only with examining the technologies in the source material, but constructing them. Creating realistic, hypothetical situations in which ideas in the book could play out.

Neal Stephenson, an author and technology consultant, wants ”big ideas” to inspire young scientists and engineers. In 2012, he partnered with the Center for Science and the Imagination (CSI) at Arizona State University to create Project Hieroglyph, a web-based project that provides ”a space for writers, scientists, artists and engineers to collaborate on creative, ambitious visions of our near future.”

Meanwhile, Jordin Kare, an astrophysicist at the Seattle-based tech company LaserMotive, has stressed that, ”Some of the people who are doing the most exploratory thinking in science have a connection to the science-fiction world.”

"It is a chicken and the egg scenario: we construct our environment, our environment constructs us."

Cory Doctorow, a novelist, activist and co-editor of the blog Boing Boing, is one such person, listing Disney and Tesla among the clients for whom he has imagined theoretical futures. ”I really like design fiction or prototyping,” he told the Smithsonian. ”There is nothing weird about a company doing this – commissioning a story about people using a technology to decide if the technology is worth following through on. It’s like an architect creating a virtual fly-through of a building.”

Most companies keep their design fiction under lock and key – part of its appeal is that it is closely guarded intellectual property. But occasionally, the public does get a glimpse.

In 2016, a video entitled The Selfish Ledger, designed for internal use only at Google, was leaked to The Verge. The conceit of The Selfish Ledger (its very title a homage to evolutionary biologist Richard Dawkins’ famous work The Selfish Gene) was that our lives are becoming increasingly recorded, and the ‘ledger’ – the digital record of our activity – will start to influence behaviour on an individual and societal level, affecting the entire species. It is a chicken and the egg scenario: we construct our environment; our environment constructs us.

Making the leap

Making the leap from traditional research and development teams to the unpredictable, unfocussed, often very un-business-like brains of writers and artists is still a leap that some companies are hesitant to take.

As more businesses start to follow the lead of big tech in trusting the instincts of societies’ biggest thinkers, the idea of design fiction is sounding less like a gamble on blue sky thinking and more like an investment in imagination.

"The idea of design fiction is starting to sound less like a gamble and more like an investment in imagination."

Watson and Freeman encourage business leaders to step outside of the here and now, if they want to avoid the self-imposed shackles that limited Karl Benz’s vision. This feeds into the discussion around the benefits of neurodiversity and balanced teams within businesses. The more diverse the inputs and ways of thinking, the more futureproof the business.

Neste’s R&D fellow, inventor Ulla Kiiski’s 1993 breakthrough into sustainable fuel involved a ‘think tank’ from outside the energy industry too – albeit in a more distributed way, through academia. Kiiski’s initial thinking came through exposure to, and interaction with, researchers, academic minds and chemistry papers that were external and went beyond Neste’s core business goals at that time. This breakthrough is a reminder that while design fiction isn’t for every business, baking in some sense of exploratory thinking – whether in the form of academic papers from adjacent disciplines, or simply broader reading and study – will help your team look beyond your business’s inherited certainties, and throw up new approaches and opportunities.

And thinking your business into the future may mean helping it to think more sustainably, too. In Toby Heaps’ words, becoming a future maker, not a future taker.

Science fiction has been challenging the way we think about the future for the past two hundred years or more. Now, rather than simply picking over the bones once it’s become public, businesses are harnessing its theoretical potential at the source.

Design fiction won’t give us answers. It won’t provide anything definitive. But as part of a suite of tools that allow better exploratory work, more authentic simulations, and more acute radar on the future in all its manifest potential, it can be of enormous value to business.

From science fiction to everyday reality

It’s not just about the iPad and AI. Here are eight of the most prescient near-future visions in science fiction.

Frank Herbert’s Dune (1965) is an ecological piece of design fiction. The imaginary planet, Arrakis, is a desert world, ravaged by expansionist humanity, despite the warnings of its ancient inhabitants that they urgently need to become ”ecologically literate” if they want their raw-material-and-refinement interplanetary export business to be sustainable. It contains words that prefigure Greta Thunberg’s recent United Nations address: ”Men and their works have been a disease on the surface of their planet. You cannot go on forever stealing what you need without regard to those who come after.”

Mobile phones, in the form of a pocket communicator with a flip-up grid antenna, began life in Star Trek (1966).

Robots play a key part in Fritz Lang’s silent epic Metropolis (1927).

Military drones strafe the sky in The Terminator (1984).

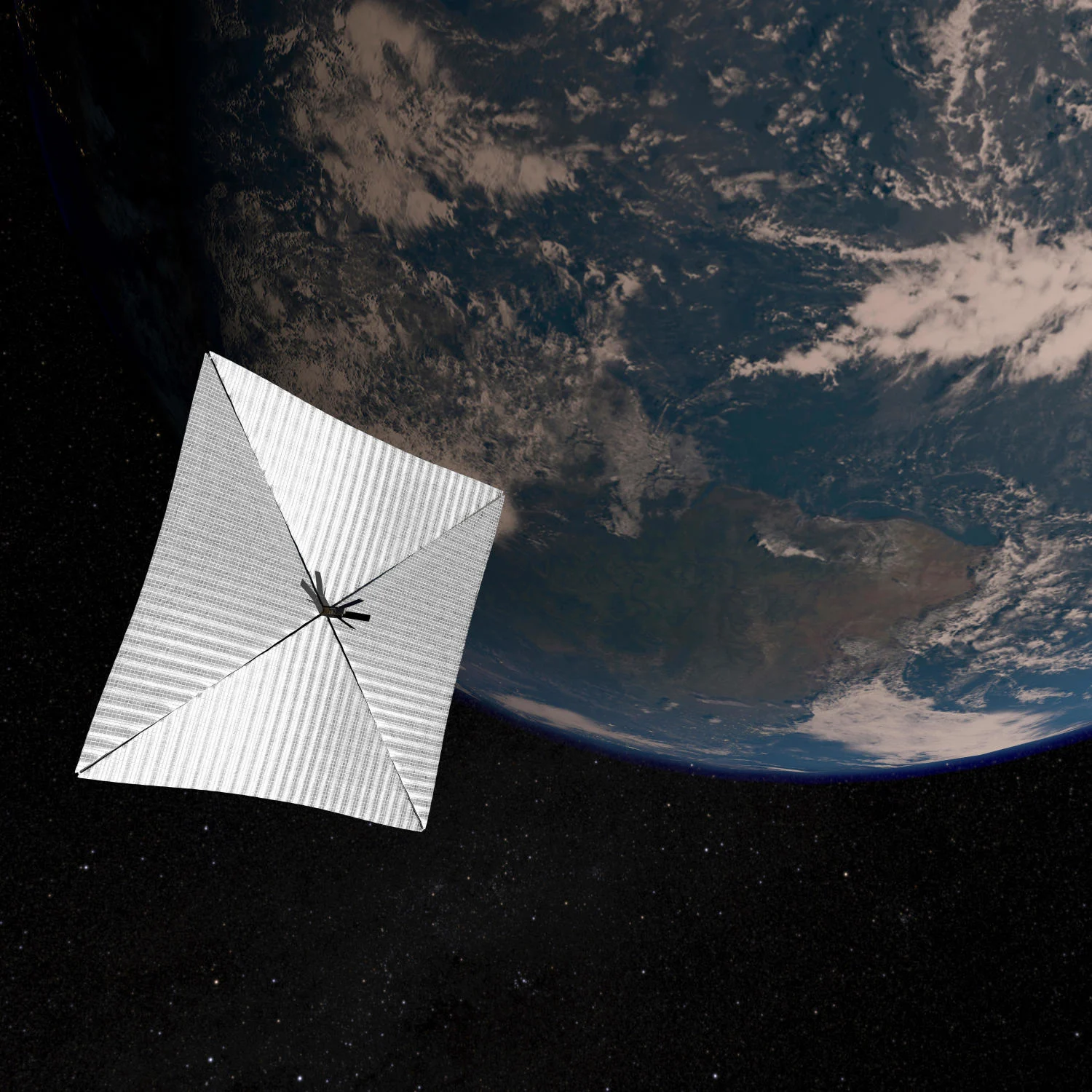

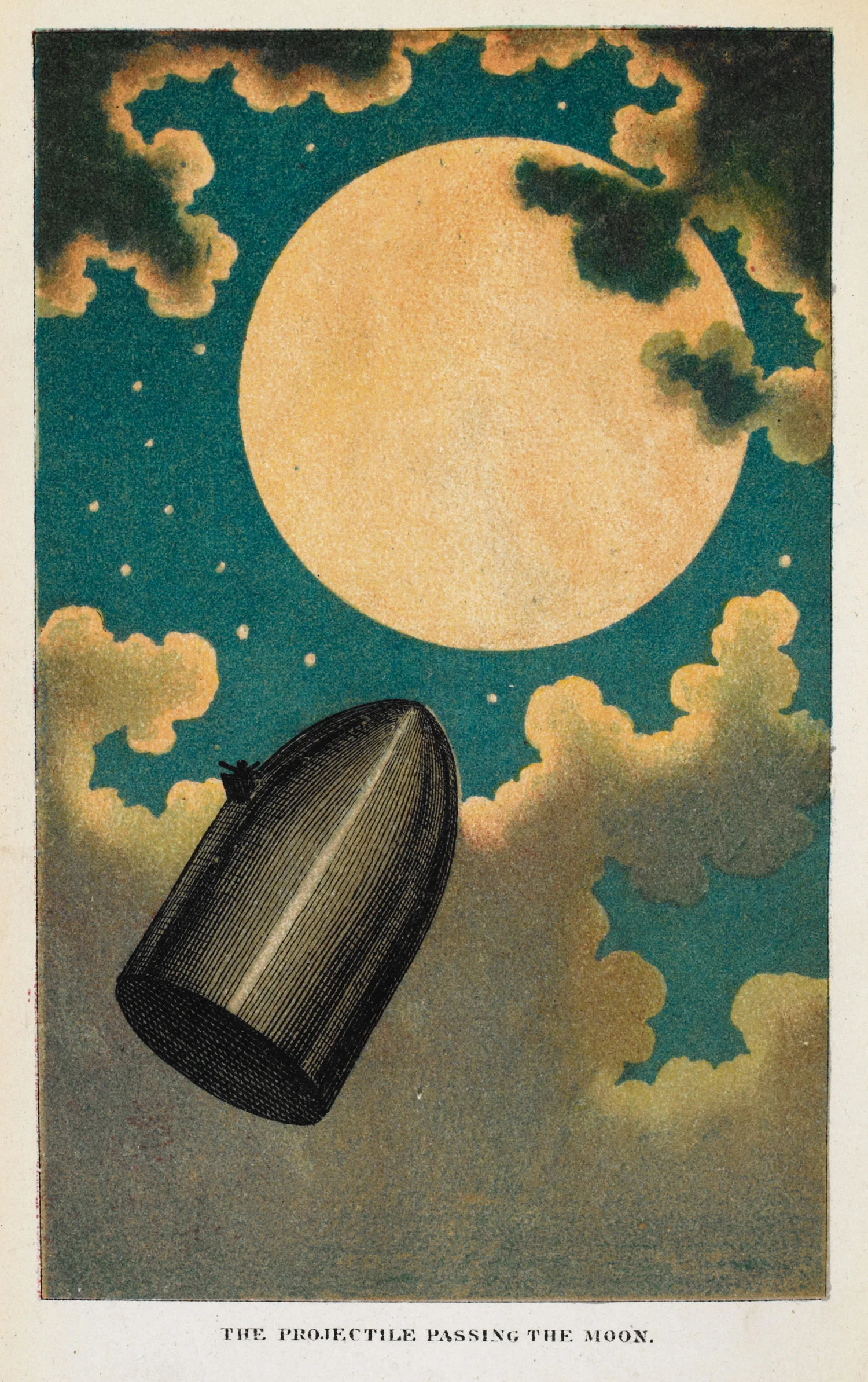

Science fiction writers have always been fascinated by sustainable fuel. Solar propulsion sails are all the rage for satellites, probes and other spacecraft, as well as some experimental aircraft. Jules Verne’s 1865 novel Earth to the Moon – famous as the early silent film Une Voyage Dans La Lune – already featured spaceships ”propelled by the light” from the sun. The spaceship in Douglas Adams’ The Hitchhiker’s Guide To The Galaxy was powered by an Improbability Drive, which generated power through the shifting balance of probabilities. While this has not led to any current advances in propulsion technology or fuel, the principles are eerily prescient of the principles underlying quantum computing.

Self-driving cars appear in another Arnold Schwarzenegger sci-fi action movie, Total Recall (1990).

Earbuds, made popular by the Apple iPod in 2001, featured in the movie Fahrenheit 451 (1966). This last was an adaptation of Ray Bradbury’s same-titled 1953 novel, and yes, wireless buds that pipe words and music directly into characters’ ear canals were present and correct there, too.

Blade Runner author Philip K Dick’s 1969 novel Ubik has enjoyed renewed fame as a key text for Silicon Valley’s technologists, especially those developing Internet of Things applications, from smart homes to driverless cars. This passage in particular helps frame one of the possible foreseeable consequences of our reliance on AI. It contains the oft-quoted passage starting, ”The door refused to open. It said, ‘Five cents, please’”, in which an apartment owner gets into a contractual argument with his networked apartment door – that just happens to talk very much like Siri and Alexa.